3. Samuelson Multiplier-Accelerator#

Contents

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon

Show code cell output

Requirement already satisfied: quantecon in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (0.7.2)

Requirement already satisfied: numba>=0.49.0 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from quantecon) (0.59.1)

Requirement already satisfied: numpy>=1.17.0 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from quantecon) (1.26.4)

Requirement already satisfied: requests in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from quantecon) (2.31.0)

Requirement already satisfied: scipy>=1.5.0 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from quantecon) (1.11.4)

Requirement already satisfied: sympy in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from quantecon) (1.12)

Requirement already satisfied: llvmlite<0.43,>=0.42.0dev0 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from numba>=0.49.0->quantecon) (0.42.0)

Requirement already satisfied: charset-normalizer<4,>=2 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from requests->quantecon) (2.0.4)

Requirement already satisfied: idna<4,>=2.5 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from requests->quantecon) (3.4)

Requirement already satisfied: urllib3<3,>=1.21.1 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from requests->quantecon) (2.0.7)

Requirement already satisfied: certifi>=2017.4.17 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from requests->quantecon) (2024.2.2)

Requirement already satisfied: mpmath>=0.19 in /home/runner/miniconda3/envs/quantecon/lib/python3.11/site-packages (from sympy->quantecon) (1.3.0)

3.1. Overview#

This lecture creates non-stochastic and stochastic versions of Paul Samuelson’s celebrated multiplier accelerator model [Samuelson, 1939].

In doing so, we extend the example of the Solow model class in our second OOP lecture.

Our objectives are to

provide a more detailed example of OOP and classes

review a famous model

review linear difference equations, both deterministic and stochastic

Let’s start with some standard imports:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (11, 5) #set default figure size

import numpy as np

We’ll also use the following for various tasks described below:

from quantecon import LinearStateSpace

import cmath

import math

import sympy

from sympy import Symbol, init_printing

from cmath import sqrt

3.1.1. Samuelson’s Model#

Samuelson used a second-order linear difference equation to represent a model of national output based on three components:

a national output identity asserting that national output or national income is the sum of consumption plus investment plus government purchases.

a Keynesian consumption function asserting that consumption at time \(t\) is equal to a constant times national output at time \(t-1\).

an investment accelerator asserting that investment at time \(t\) equals a constant called the accelerator coefficient times the difference in output between period \(t-1\) and \(t-2\).

Consumption plus investment plus government purchases constitute aggregate demand, which automatically calls forth an equal amount of aggregate supply.

(To read about linear difference equations see here or chapter IX of [Sargent, 1987].)

Samuelson used the model to analyze how particular values of the marginal propensity to consume and the accelerator coefficient might give rise to transient business cycles in national output.

Possible dynamic properties include

smooth convergence to a constant level of output

damped business cycles that eventually converge to a constant level of output

persistent business cycles that neither dampen nor explode

Later we present an extension that adds a random shock to the right side of the national income identity representing random fluctuations in aggregate demand.

This modification makes national output become governed by a second-order stochastic linear difference equation that, with appropriate parameter values, gives rise to recurrent irregular business cycles.

(To read about stochastic linear difference equations see chapter XI of [Sargent, 1987].)

3.2. Details#

Let’s assume that

\(\{G_t\}\) is a sequence of levels of government expenditures – we’ll start by setting \(G_t = G\) for all \(t\).

\(\{C_t\}\) is a sequence of levels of aggregate consumption expenditures, a key endogenous variable in the model.

\(\{I_t\}\) is a sequence of rates of investment, another key endogenous variable.

\(\{Y_t\}\) is a sequence of levels of national income, yet another endogenous variable.

\(a\) is the marginal propensity to consume in the Keynesian consumption function \(C_t = a Y_{t-1} + \gamma\).

\(b\) is the “accelerator coefficient” in the “investment accelerator” \(I_t = b (Y_{t-1} - Y_{t-2})\).

\(\{\epsilon_{t}\}\) is an IID sequence standard normal random variables.

\(\sigma \geq 0\) is a “volatility” parameter — setting \(\sigma = 0\) recovers the non-stochastic case that we’ll start with.

The model combines the consumption function

with the investment accelerator

and the national income identity

The parameter \(a\) is peoples’ marginal propensity to consume out of income - equation (3.1) asserts that people consume a fraction of \(a \in (0,1)\) of each additional dollar of income.

The parameter \(b > 0\) is the investment accelerator coefficient - equation (3.2) asserts that people invest in physical capital when income is increasing and disinvest when it is decreasing.

Equations (3.1), (3.2), and (3.3) imply the following second-order linear difference equation for national income:

or

where \(\rho_1 = (a+b)\) and \(\rho_2 = -b\).

To complete the model, we require two initial conditions.

If the model is to generate time series for \(t=0, \ldots, T\), we require initial values

We’ll ordinarily set the parameters \((a,b)\) so that starting from an arbitrary pair of initial conditions \((\bar Y_{-1}, \bar Y_{-2})\), national income \(Y_t\) converges to a constant value as \(t\) becomes large.

We are interested in studying

the transient fluctuations in \(Y_t\) as it converges to its steady state level

the rate at which it converges to a steady state level

The deterministic version of the model described so far — meaning that no random shocks hit aggregate demand — has only transient fluctuations.

We can convert the model to one that has persistent irregular fluctuations by adding a random shock to aggregate demand.

3.2.1. Stochastic Version of the Model#

We create a random or stochastic version of the model by adding a random process of shocks or disturbances \(\{\sigma \epsilon_t \}\) to the right side of equation (3.4), leading to the second-order scalar linear stochastic difference equation:

3.2.2. Mathematical Analysis of the Model#

To get started, let’s set \(G_t \equiv 0\), \(\sigma = 0\), and \(\gamma = 0\).

Then we can write equation (3.5) as

or

To discover the properties of the solution of (3.6), it is useful first to form the characteristic polynomial for (3.6):

where \(z\) is possibly a complex number.

We want to find the two zeros (a.k.a. roots) – namely \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) – of the characteristic polynomial.

These are two special values of \(z\), say \(z= \lambda_1\) and \(z= \lambda_2\), such that if we set \(z\) equal to one of these values in expression (3.7), the characteristic polynomial (3.7) equals zero:

Equation (3.8) is said to factor the characteristic polynomial.

When the roots are complex, they will occur as a complex conjugate pair.

When the roots are complex, it is convenient to represent them in the polar form

where \(r\) is the amplitude of the complex number and \(\omega\) is its angle or phase.

These can also be represented as

(To read about the polar form, see here)

Given initial conditions \(Y_{-1}, Y_{-2}\), we want to generate a solution of the difference equation (3.6).

It can be represented as

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants that depend on the two initial conditions and on \(\rho_1, \rho_2\).

When the roots are complex, it is useful to pursue the following calculations.

Notice that

The only way that \(Y_t\) can be a real number for each \(t\) is if \(c_1 + c_2\) is a real number and \(c_1 - c_2\) is an imaginary number.

This happens only when \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are complex conjugates, in which case they can be written in the polar forms

So we can write

where \(v\) and \(\theta\) are constants that must be chosen to satisfy initial conditions for \(Y_{-1}, Y_{-2}\).

This formula shows that when the roots are complex, \(Y_t\) displays oscillations with period \(\check p = \frac{2 \pi}{\omega}\) and damping factor \(r\).

We say that \(\check p\) is the period because in that amount of time the cosine wave \(\cos(\omega t + \theta)\) goes through exactly one complete cycles.

(Draw a cosine function to convince yourself of this please)

Remark: Following [Samuelson, 1939], we want to choose the parameters \(a, b\) of the model so that the absolute values (of the possibly complex) roots \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) of the characteristic polynomial are both strictly less than one:

Remark: When both roots \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) of the characteristic polynomial have absolute values strictly less than one, the absolute value of the larger one governs the rate of convergence to the steady state of the non stochastic version of the model.

3.2.3. Things This Lecture Does#

We write a function to generate simulations of a \(\{Y_t\}\) sequence as a function of time.

The function requires that we put in initial conditions for \(Y_{-1}, Y_{-2}\).

The function checks that \(a, b\) are set so that \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) are less than unity in absolute value (also called “modulus”).

The function also tells us whether the roots are complex, and, if they are complex, returns both their real and complex parts.

If the roots are both real, the function returns their values.

We use our function written to simulate paths that are stochastic (when \(\sigma >0\)).

We have written the function in a way that allows us to input \(\{G_t\}\) paths of a few simple forms, e.g.,

one time jumps in \(G\) at some time

a permanent jump in \(G\) that occurs at some time

We proceed to use the Samuelson multiplier-accelerator model as a laboratory to make a simple OOP example.

The “state” that determines next period’s \(Y_{t+1}\) is now not just the current value \(Y_t\) but also the once lagged value \(Y_{t-1}\).

This involves a little more bookkeeping than is required in the Solow model class definition.

We use the Samuelson multiplier-accelerator model as a vehicle for teaching how we can gradually add more features to the class.

We want to have a method in the class that automatically generates a simulation, either non-stochastic (\(\sigma=0\)) or stochastic (\(\sigma > 0\)).

We also show how to map the Samuelson model into a simple instance of the LinearStateSpace class described here.

We can use a LinearStateSpace instance to do various things that we did above with our homemade function and class.

Among other things, we show by example that the eigenvalues of the matrix \(A\) that we use to form the instance of the LinearStateSpace class for the Samuelson model equal the roots of the characteristic polynomial (3.7) for the Samuelson multiplier accelerator model.

Here is the formula for the matrix \(A\) in the linear state space system in the case that government expenditures are a constant \(G\):

3.3. Implementation#

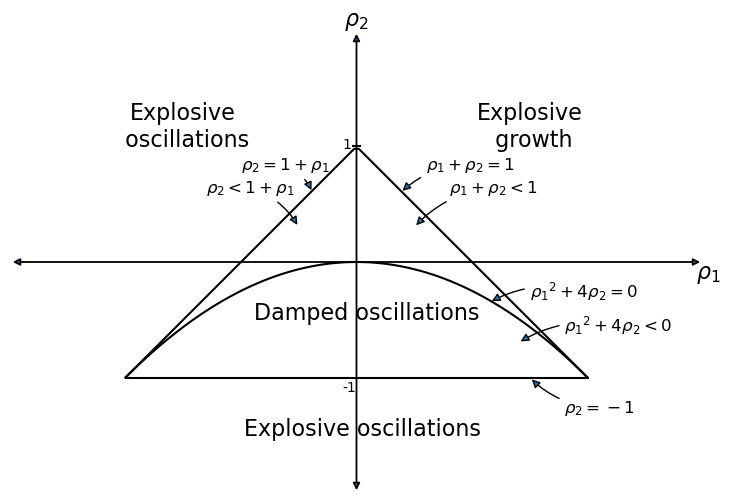

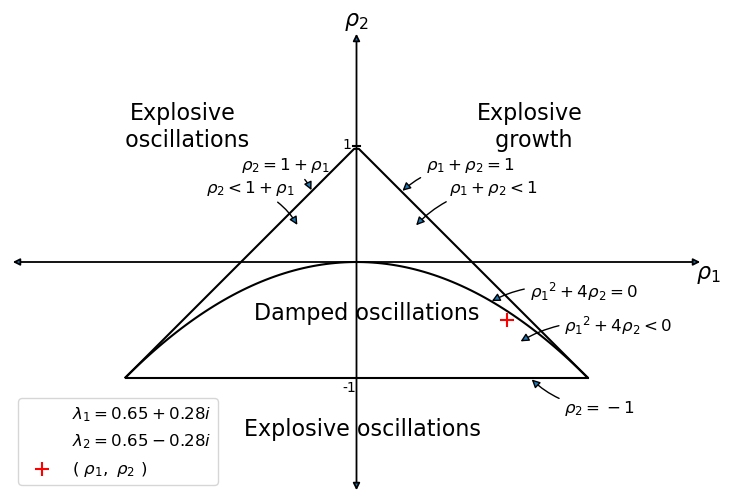

We’ll start by drawing an informative graph from page 189 of [Sargent, 1987]

def param_plot():

"""This function creates the graph on page 189 of

Sargent Macroeconomic Theory, second edition, 1987.

"""

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.set_aspect('equal')

# Set axis

xmin, ymin = -3, -2

xmax, ymax = -xmin, -ymin

plt.axis([xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax])

# Set axis labels

ax.set(xticks=[], yticks=[])

ax.set_xlabel(r'$\rho_2$', fontsize=16)

ax.xaxis.set_label_position('top')

ax.set_ylabel(r'$\rho_1$', rotation=0, fontsize=16)

ax.yaxis.set_label_position('right')

# Draw (t1, t2) points

ρ1 = np.linspace(-2, 2, 100)

ax.plot(ρ1, -abs(ρ1) + 1, c='black')

ax.plot(ρ1, np.full_like(ρ1, -1), c='black')

ax.plot(ρ1, -(ρ1**2 / 4), c='black')

# Turn normal axes off

for spine in ['left', 'bottom', 'top', 'right']:

ax.spines[spine].set_visible(False)

# Add arrows to represent axes

axes_arrows = {'arrowstyle': '<|-|>', 'lw': 1.3}

ax.annotate('', xy=(xmin, 0), xytext=(xmax, 0), arrowprops=axes_arrows)

ax.annotate('', xy=(0, ymin), xytext=(0, ymax), arrowprops=axes_arrows)

# Annotate the plot with equations

plot_arrowsl = {'arrowstyle': '-|>', 'connectionstyle': "arc3, rad=-0.2"}

plot_arrowsr = {'arrowstyle': '-|>', 'connectionstyle': "arc3, rad=0.2"}

ax.annotate(r'$\rho_1 + \rho_2 < 1$', xy=(0.5, 0.3), xytext=(0.8, 0.6),

arrowprops=plot_arrowsr, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'$\rho_1 + \rho_2 = 1$', xy=(0.38, 0.6), xytext=(0.6, 0.8),

arrowprops=plot_arrowsr, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'$\rho_2 < 1 + \rho_1$', xy=(-0.5, 0.3), xytext=(-1.3, 0.6),

arrowprops=plot_arrowsl, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'$\rho_2 = 1 + \rho_1$', xy=(-0.38, 0.6), xytext=(-1, 0.8),

arrowprops=plot_arrowsl, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'$\rho_2 = -1$', xy=(1.5, -1), xytext=(1.8, -1.3),

arrowprops=plot_arrowsl, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'${\rho_1}^2 + 4\rho_2 = 0$', xy=(1.15, -0.35),

xytext=(1.5, -0.3), arrowprops=plot_arrowsr, fontsize='12')

ax.annotate(r'${\rho_1}^2 + 4\rho_2 < 0$', xy=(1.4, -0.7),

xytext=(1.8, -0.6), arrowprops=plot_arrowsr, fontsize='12')

# Label categories of solutions

ax.text(1.5, 1, 'Explosive\n growth', ha='center', fontsize=16)

ax.text(-1.5, 1, 'Explosive\n oscillations', ha='center', fontsize=16)

ax.text(0.05, -1.5, 'Explosive oscillations', ha='center', fontsize=16)

ax.text(0.09, -0.5, 'Damped oscillations', ha='center', fontsize=16)

# Add small marker to y-axis

ax.axhline(y=1.005, xmin=0.495, xmax=0.505, c='black')

ax.text(-0.12, -1.12, '-1', fontsize=10)

ax.text(-0.12, 0.98, '1', fontsize=10)

return fig

param_plot()

plt.show()

The graph portrays regions in which the \((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) root pairs implied by the \((\rho_1 = (a+b), \rho_2 = - b)\) difference equation parameter pairs in the Samuelson model are such that:

\((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) are complex with modulus less than \(1\) - in this case, the \(\{Y_t\}\) sequence displays damped oscillations.

\((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) are both real, but one is strictly greater than \(1\) - this leads to explosive growth.

\((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) are both real, but one is strictly less than \(-1\) - this leads to explosive oscillations.

\((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) are both real and both are less than \(1\) in absolute value - in this case, there is smooth convergence to the steady state without damped cycles.

Later we’ll present the graph with a red mark showing the particular point implied by the setting of \((a,b)\).

3.3.1. Function to Describe Implications of Characteristic Polynomial#

def categorize_solution(ρ1, ρ2):

"""This function takes values of ρ1 and ρ2 and uses them

to classify the type of solution

"""

discriminant = ρ1 ** 2 + 4 * ρ2

if ρ2 > 1 + ρ1 or ρ2 < -1:

print('Explosive oscillations')

elif ρ1 + ρ2 > 1:

print('Explosive growth')

elif discriminant < 0:

print('Roots are complex with modulus less than one; \

therefore damped oscillations')

else:

print('Roots are real and absolute values are less than one; \

therefore get smooth convergence to a steady state')

### Test the categorize_solution function

categorize_solution(1.3, -.4)

Roots are real and absolute values are less than one; therefore get smooth convergence to a steady state

3.3.2. Function for Plotting Paths#

A useful function for our work below is

def plot_y(function=None):

"""Function plots path of Y_t"""

plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(function)

plt.xlabel('Time $t$')

plt.ylabel('$Y_t$', rotation=0)

plt.grid()

plt.show()

3.3.3. Manual or “by hand” Root Calculations#

The following function calculates roots of the characteristic polynomial using high school algebra.

(We’ll calculate the roots in other ways later)

The function also plots a \(Y_t\) starting from initial conditions that we set

# This is a 'manual' method

def y_nonstochastic(y_0=100, y_1=80, α=.92, β=.5, γ=10, n=80):

"""Takes values of parameters and computes the roots of characteristic

polynomial. It tells whether they are real or complex and whether they

are less than unity in absolute value.It also computes a simulation of

length n starting from the two given initial conditions for national

income

"""

roots = []

ρ1 = α + β

ρ2 = -β

print(f'ρ_1 is {ρ1}')

print(f'ρ_2 is {ρ2}')

discriminant = ρ1 ** 2 + 4 * ρ2

if discriminant == 0:

roots.append(-ρ1 / 2)

print('Single real root: ')

print(''.join(str(roots)))

elif discriminant > 0:

roots.append((-ρ1 + sqrt(discriminant).real) / 2)

roots.append((-ρ1 - sqrt(discriminant).real) / 2)

print('Two real roots: ')

print(''.join(str(roots)))

else:

roots.append((-ρ1 + sqrt(discriminant)) / 2)

roots.append((-ρ1 - sqrt(discriminant)) / 2)

print('Two complex roots: ')

print(''.join(str(roots)))

if all(abs(root) < 1 for root in roots):

print('Absolute values of roots are less than one')

else:

print('Absolute values of roots are not less than one')

def transition(x, t): return ρ1 * x[t - 1] + ρ2 * x[t - 2] + γ

y_t = [y_0, y_1]

for t in range(2, n):

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t))

return y_t

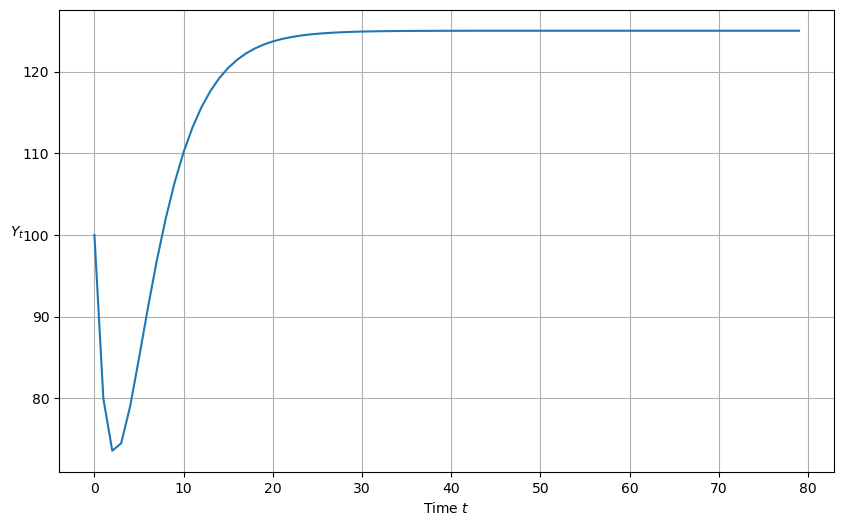

plot_y(y_nonstochastic())

ρ_1 is 1.42

ρ_2 is -0.5

Two real roots:

[-0.6459687576256715, -0.7740312423743284]

Absolute values of roots are less than one

3.3.4. Reverse-Engineering Parameters to Generate Damped Cycles#

The next cell writes code that takes as inputs the modulus \(r\) and phase \(\phi\) of a conjugate pair of complex numbers in polar form

The code assumes that these two complex numbers are the roots of the characteristic polynomial

It then reverse-engineers \((a,b)\) and \((\rho_1, \rho_2)\), pairs that would generate those roots

### code to reverse-engineer a cycle

### y_t = r^t (c_1 cos(ϕ t) + c2 sin(ϕ t))

###

def f(r, ϕ):

"""

Takes modulus r and angle ϕ of complex number r exp(j ϕ)

and creates ρ1 and ρ2 of characteristic polynomial for which

r exp(j ϕ) and r exp(- j ϕ) are complex roots.

Returns the multiplier coefficient a and the accelerator coefficient b

that verifies those roots.

"""

g1 = cmath.rect(r, ϕ) # Generate two complex roots

g2 = cmath.rect(r, -ϕ)

ρ1 = g1 + g2 # Implied ρ1, ρ2

ρ2 = -g1 * g2

b = -ρ2 # Reverse-engineer a and b that validate these

a = ρ1 - b

return ρ1, ρ2, a, b

## Now let's use the function in an example

## Here are the example parameters

r = .95

period = 10 # Length of cycle in units of time

ϕ = 2 * math.pi/period

## Apply the function

ρ1, ρ2, a, b = f(r, ϕ)

print(f"a, b = {a}, {b}")

print(f"ρ1, ρ2 = {ρ1}, {ρ2}")

a, b = (0.6346322893124001+0j), (0.9024999999999999-0j)

ρ1, ρ2 = (1.5371322893124+0j), (-0.9024999999999999+0j)

## Print the real components of ρ1 and ρ2

ρ1 = ρ1.real

ρ2 = ρ2.real

ρ1, ρ2

(1.5371322893124, -0.9024999999999999)

3.3.5. Root Finding Using Numpy#

Here we’ll use numpy to compute the roots of the characteristic polynomial

r1, r2 = np.roots([1, -ρ1, -ρ2])

p1 = cmath.polar(r1)

p2 = cmath.polar(r2)

print(f"r, ϕ = {r}, {ϕ}")

print(f"p1, p2 = {p1}, {p2}")

# print(f"g1, g2 = {g1}, {g2}")

print(f"a, b = {a}, {b}")

print(f"ρ1, ρ2 = {ρ1}, {ρ2}")

r, ϕ = 0.95, 0.6283185307179586

p1, p2 = (0.95, 0.6283185307179586), (0.95, -0.6283185307179586)

a, b = (0.6346322893124001+0j), (0.9024999999999999-0j)

ρ1, ρ2 = 1.5371322893124, -0.9024999999999999

##=== This method uses numpy to calculate roots ===#

def y_nonstochastic(y_0=100, y_1=80, α=.9, β=.8, γ=10, n=80):

""" Rather than computing the roots of the characteristic

polynomial by hand as we did earlier, this function

enlists numpy to do the work for us

"""

# Useful constants

ρ1 = α + β

ρ2 = -β

categorize_solution(ρ1, ρ2)

# Find roots of polynomial

roots = np.roots([1, -ρ1, -ρ2])

print(f'Roots are {roots}')

# Check if real or complex

if all(isinstance(root, complex) for root in roots):

print('Roots are complex')

else:

print('Roots are real')

# Check if roots are less than one

if all(abs(root) < 1 for root in roots):

print('Roots are less than one')

else:

print('Roots are not less than one')

# Define transition equation

def transition(x, t): return ρ1 * x[t - 1] + ρ2 * x[t - 2] + γ

# Set initial conditions

y_t = [y_0, y_1]

# Generate y_t series

for t in range(2, n):

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t))

return y_t

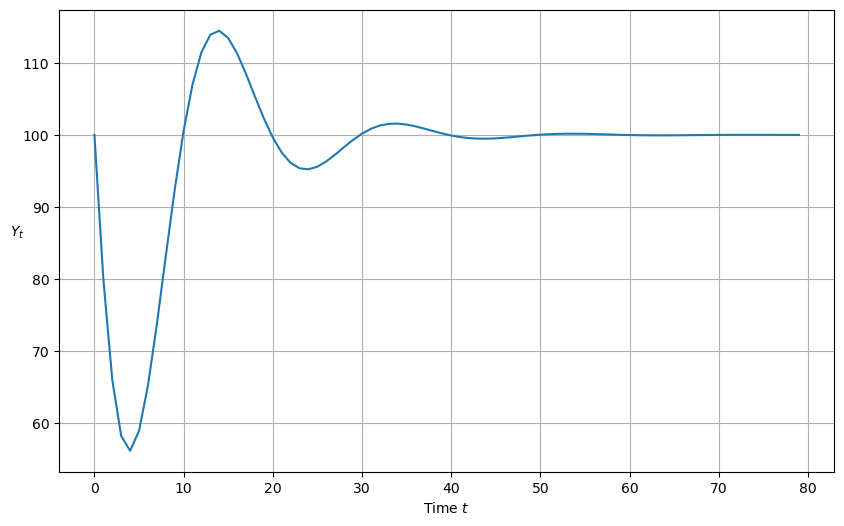

plot_y(y_nonstochastic())

Roots are complex with modulus less than one; therefore damped oscillations

Roots are [0.85+0.27838822j 0.85-0.27838822j]

Roots are complex

Roots are less than one

3.3.6. Reverse-Engineered Complex Roots: Example#

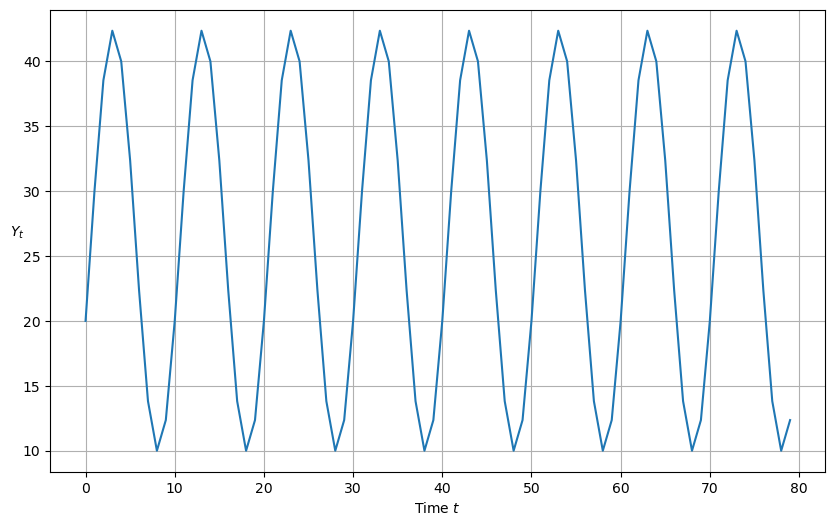

The next cell studies the implications of reverse-engineered complex roots.

We’ll generate an undamped cycle of period 10

r = 1 # Generates undamped, nonexplosive cycles

period = 10 # Length of cycle in units of time

ϕ = 2 * math.pi/period

## Apply the reverse-engineering function f

ρ1, ρ2, a, b = f(r, ϕ)

# Drop the imaginary part so that it is a valid input into y_nonstochastic

a = a.real

b = b.real

print(f"a, b = {a}, {b}")

ytemp = y_nonstochastic(α=a, β=b, y_0=20, y_1=30)

plot_y(ytemp)

a, b = 0.6180339887498949, 1.0

Roots are complex with modulus less than one; therefore damped oscillations

Roots are [0.80901699+0.58778525j 0.80901699-0.58778525j]

Roots are complex

Roots are less than one

3.3.7. Digression: Using Sympy to Find Roots#

We can also use sympy to compute analytic formulas for the roots

init_printing()

r1 = Symbol("ρ_1")

r2 = Symbol("ρ_2")

z = Symbol("z")

sympy.solve(z**2 - r1*z - r2, z)

a = Symbol("α")

b = Symbol("β")

r1 = a + b

r2 = -b

sympy.solve(z**2 - r1*z - r2, z)

3.4. Stochastic Shocks#

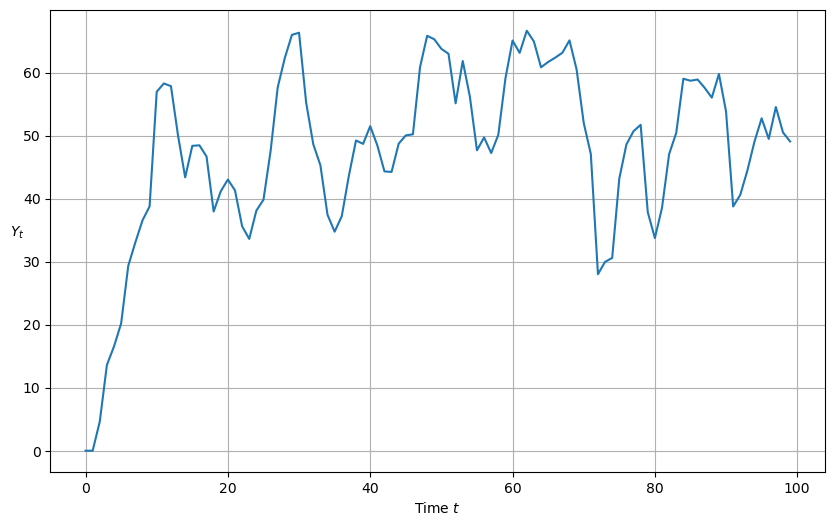

Now we’ll construct some code to simulate the stochastic version of the model that emerges when we add a random shock process to aggregate demand

def y_stochastic(y_0=0, y_1=0, α=0.8, β=0.2, γ=10, n=100, σ=5):

"""This function takes parameters of a stochastic version of

the model and proceeds to analyze the roots of the characteristic

polynomial and also generate a simulation.

"""

# Useful constants

ρ1 = α + β

ρ2 = -β

# Categorize solution

categorize_solution(ρ1, ρ2)

# Find roots of polynomial

roots = np.roots([1, -ρ1, -ρ2])

print(roots)

# Check if real or complex

if all(isinstance(root, complex) for root in roots):

print('Roots are complex')

else:

print('Roots are real')

# Check if roots are less than one

if all(abs(root) < 1 for root in roots):

print('Roots are less than one')

else:

print('Roots are not less than one')

# Generate shocks

ϵ = np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

# Define transition equation

def transition(x, t): return ρ1 * \

x[t - 1] + ρ2 * x[t - 2] + γ + σ * ϵ[t]

# Set initial conditions

y_t = [y_0, y_1]

# Generate y_t series

for t in range(2, n):

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t))

return y_t

plot_y(y_stochastic())

Roots are real and absolute values are less than one; therefore get smooth convergence to a steady state

[0.7236068 0.2763932]

Roots are real

Roots are less than one

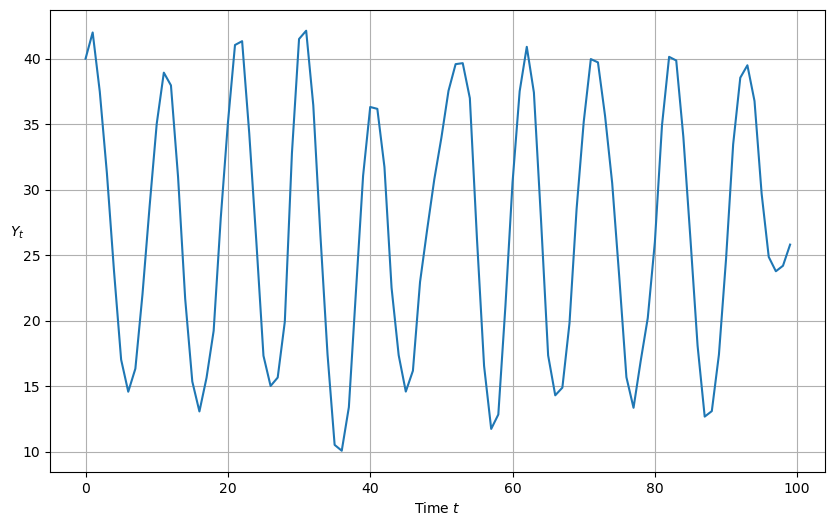

Let’s do a simulation in which there are shocks and the characteristic polynomial has complex roots

r = .97

period = 10 # Length of cycle in units of time

ϕ = 2 * math.pi/period

### Apply the reverse-engineering function f

ρ1, ρ2, a, b = f(r, ϕ)

# Drop the imaginary part so that it is a valid input into y_nonstochastic

a = a.real

b = b.real

print(f"a, b = {a}, {b}")

plot_y(y_stochastic(y_0=40, y_1 = 42, α=a, β=b, σ=2, n=100))

a, b = 0.6285929690873979, 0.9409000000000001

Roots are complex with modulus less than one; therefore damped oscillations

[0.78474648+0.57015169j 0.78474648-0.57015169j]

Roots are complex

Roots are less than one

3.5. Government Spending#

This function computes a response to either a permanent or one-off increase in government expenditures

def y_stochastic_g(y_0=20,

y_1=20,

α=0.8,

β=0.2,

γ=10,

n=100,

σ=2,

g=0,

g_t=0,

duration='permanent'):

"""This program computes a response to a permanent increase

in government expenditures that occurs at time 20

"""

# Useful constants

ρ1 = α + β

ρ2 = -β

# Categorize solution

categorize_solution(ρ1, ρ2)

# Find roots of polynomial

roots = np.roots([1, -ρ1, -ρ2])

print(roots)

# Check if real or complex

if all(isinstance(root, complex) for root in roots):

print('Roots are complex')

else:

print('Roots are real')

# Check if roots are less than one

if all(abs(root) < 1 for root in roots):

print('Roots are less than one')

else:

print('Roots are not less than one')

# Generate shocks

ϵ = np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

def transition(x, t, g):

# Non-stochastic - separated to avoid generating random series

# when not needed

if σ == 0:

return ρ1 * x[t - 1] + ρ2 * x[t - 2] + γ + g

# Stochastic

else:

ϵ = np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

return ρ1 * x[t - 1] + ρ2 * x[t - 2] + γ + g + σ * ϵ[t]

# Create list and set initial conditions

y_t = [y_0, y_1]

# Generate y_t series

for t in range(2, n):

# No government spending

if g == 0:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t))

# Government spending (no shock)

elif g != 0 and duration == None:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t))

# Permanent government spending shock

elif duration == 'permanent':

if t < g_t:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t, g=0))

else:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t, g=g))

# One-off government spending shock

elif duration == 'one-off':

if t == g_t:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t, g=g))

else:

y_t.append(transition(y_t, t, g=0))

return y_t

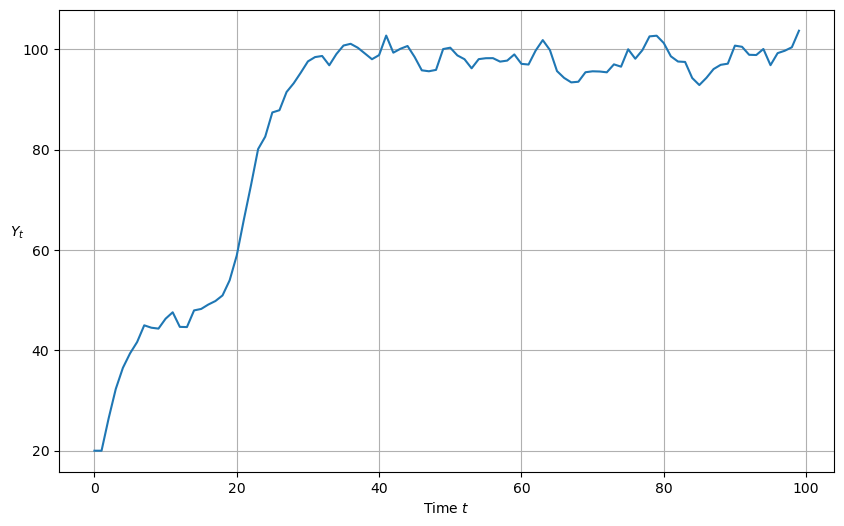

A permanent government spending shock can be simulated as follows

plot_y(y_stochastic_g(g=10, g_t=20, duration='permanent'))

Roots are real and absolute values are less than one; therefore get smooth convergence to a steady state

[0.7236068 0.2763932]

Roots are real

Roots are less than one

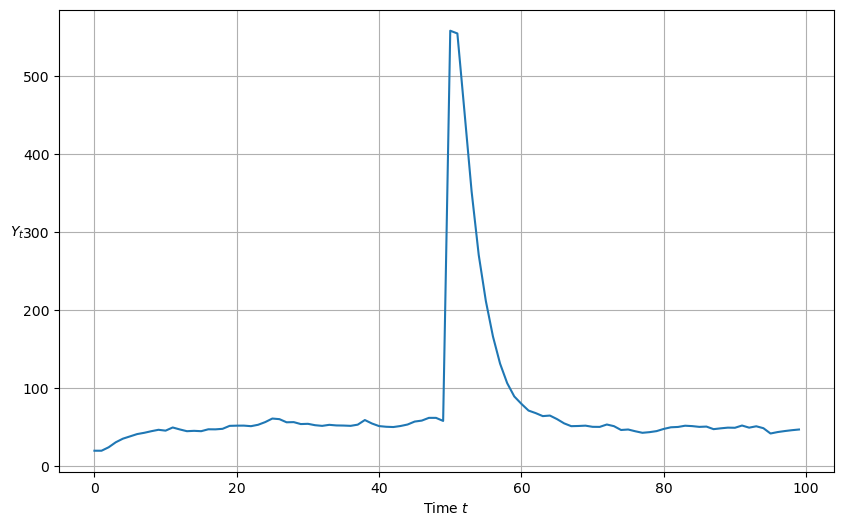

We can also see the response to a one time jump in government expenditures

plot_y(y_stochastic_g(g=500, g_t=50, duration='one-off'))

Roots are real and absolute values are less than one; therefore get smooth convergence to a steady state

[0.7236068 0.2763932]

Roots are real

Roots are less than one

3.6. Wrapping Everything Into a Class#

Up to now, we have written functions to do the work.

Now we’ll roll up our sleeves and write a Python class called Samuelson

for the Samuelson model

class Samuelson():

"""This class represents the Samuelson model, otherwise known as the

multiple-accelerator model. The model combines the Keynesian multiplier

with the accelerator theory of investment.

The path of output is governed by a linear second-order difference equation

.. math::

Y_t = + \alpha (1 + \beta) Y_{t-1} - \alpha \beta Y_{t-2}

Parameters

----------

y_0 : scalar

Initial condition for Y_0

y_1 : scalar

Initial condition for Y_1

α : scalar

Marginal propensity to consume

β : scalar

Accelerator coefficient

n : int

Number of iterations

σ : scalar

Volatility parameter. It must be greater than or equal to 0. Set

equal to 0 for a non-stochastic model.

g : scalar

Government spending shock

g_t : int

Time at which government spending shock occurs. Must be specified

when duration != None.

duration : {None, 'permanent', 'one-off'}

Specifies type of government spending shock. If none, government

spending equal to g for all t.

"""

def __init__(self,

y_0=100,

y_1=50,

α=1.3,

β=0.2,

γ=10,

n=100,

σ=0,

g=0,

g_t=0,

duration=None):

self.y_0, self.y_1, self.α, self.β = y_0, y_1, α, β

self.n, self.g, self.g_t, self.duration = n, g, g_t, duration

self.γ, self.σ = γ, σ

self.ρ1 = α + β

self.ρ2 = -β

self.roots = np.roots([1, -self.ρ1, -self.ρ2])

def root_type(self):

if all(isinstance(root, complex) for root in self.roots):

return 'Complex conjugate'

elif len(self.roots) > 1:

return 'Double real'

else:

return 'Single real'

def root_less_than_one(self):

if all(abs(root) < 1 for root in self.roots):

return True

def solution_type(self):

ρ1, ρ2 = self.ρ1, self.ρ2

discriminant = ρ1 ** 2 + 4 * ρ2

if ρ2 >= 1 + ρ1 or ρ2 <= -1:

return 'Explosive oscillations'

elif ρ1 + ρ2 >= 1:

return 'Explosive growth'

elif discriminant < 0:

return 'Damped oscillations'

else:

return 'Steady state'

def _transition(self, x, t, g):

# Non-stochastic - separated to avoid generating random series

# when not needed

if self.σ == 0:

return self.ρ1 * x[t - 1] + self.ρ2 * x[t - 2] + self.γ + g

# Stochastic

else:

ϵ = np.random.normal(0, 1, self.n)

return self.ρ1 * x[t - 1] + self.ρ2 * x[t - 2] + self.γ + g \

+ self.σ * ϵ[t]

def generate_series(self):

# Create list and set initial conditions

y_t = [self.y_0, self.y_1]

# Generate y_t series

for t in range(2, self.n):

# No government spending

if self.g == 0:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t))

# Government spending (no shock)

elif self.g != 0 and self.duration == None:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t))

# Permanent government spending shock

elif self.duration == 'permanent':

if t < self.g_t:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t, g=0))

else:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t, g=self.g))

# One-off government spending shock

elif self.duration == 'one-off':

if t == self.g_t:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t, g=self.g))

else:

y_t.append(self._transition(y_t, t, g=0))

return y_t

def summary(self):

print('Summary\n' + '-' * 50)

print(f'Root type: {self.root_type()}')

print(f'Solution type: {self.solution_type()}')

print(f'Roots: {str(self.roots)}')

if self.root_less_than_one() == True:

print('Absolute value of roots is less than one')

else:

print('Absolute value of roots is not less than one')

if self.σ > 0:

print('Stochastic series with σ = ' + str(self.σ))

else:

print('Non-stochastic series')

if self.g != 0:

print('Government spending equal to ' + str(self.g))

if self.duration != None:

print(self.duration.capitalize() +

' government spending shock at t = ' + str(self.g_t))

def plot(self):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.plot(self.generate_series())

ax.set(xlabel='Iteration', xlim=(0, self.n))

ax.set_ylabel('$Y_t$', rotation=0)

ax.grid()

# Add parameter values to plot

paramstr = f'$\\alpha={self.α:.2f}$ \n $\\beta={self.β:.2f}$ \n \

$\\gamma={self.γ:.2f}$ \n $\\sigma={self.σ:.2f}$ \n \

$\\rho_1={self.ρ1:.2f}$ \n $\\rho_2={self.ρ2:.2f}$'

props = dict(fc='white', pad=10, alpha=0.5)

ax.text(0.87, 0.05, paramstr, transform=ax.transAxes,

fontsize=12, bbox=props, va='bottom')

return fig

def param_plot(self):

# Uses the param_plot() function defined earlier (it is then able

# to be used standalone or as part of the model)

fig = param_plot()

ax = fig.gca()

# Add λ values to legend

for i, root in enumerate(self.roots):

if isinstance(root, complex):

# Need to fill operator for positive as string is split apart

operator = ['+', '']

label = rf'$\lambda_{i+1} = {sam.roots[i].real:.2f} {operator[i]} {sam.roots[i].imag:.2f}i$'

else:

label = rf'$\lambda_{i+1} = {sam.roots[i].real:.2f}$'

ax.scatter(0, 0, 0, label=label) # dummy to add to legend

# Add ρ pair to plot

ax.scatter(self.ρ1, self.ρ2, 100, 'red', '+',

label=r'$(\ \rho_1, \ \rho_2 \ )$', zorder=5)

plt.legend(fontsize=12, loc=3)

return fig

3.6.1. Illustration of Samuelson Class#

Now we’ll put our Samuelson class to work on an example

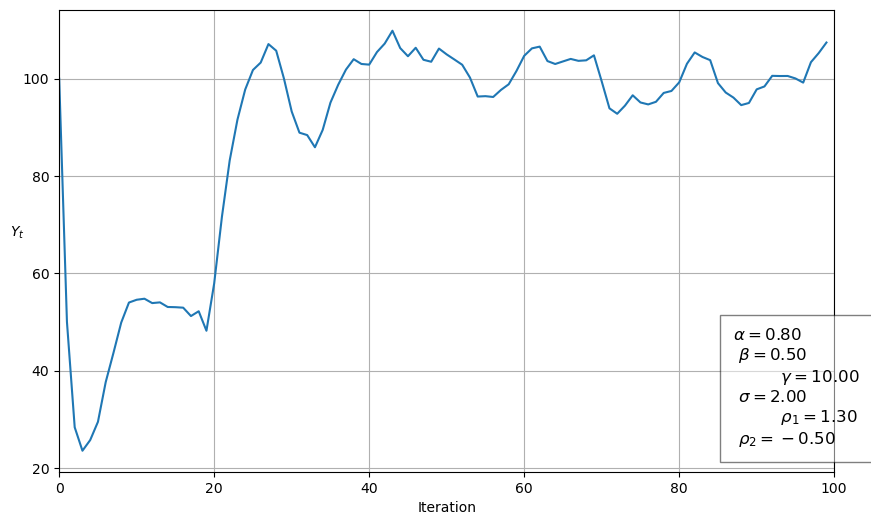

sam = Samuelson(α=0.8, β=0.5, σ=2, g=10, g_t=20, duration='permanent')

sam.summary()

Summary

--------------------------------------------------

Root type: Complex conjugate

Solution type: Damped oscillations

Roots: [0.65+0.27838822j 0.65-0.27838822j]

Absolute value of roots is less than one

Stochastic series with σ = 2

Government spending equal to 10

Permanent government spending shock at t = 20

sam.plot()

plt.show()

3.6.2. Using the Graph#

We’ll use our graph to show where the roots lie and how their location is consistent with the behavior of the path just graphed.

The red \(+\) sign shows the location of the roots

sam.param_plot()

plt.show()

3.7. Using the LinearStateSpace Class#

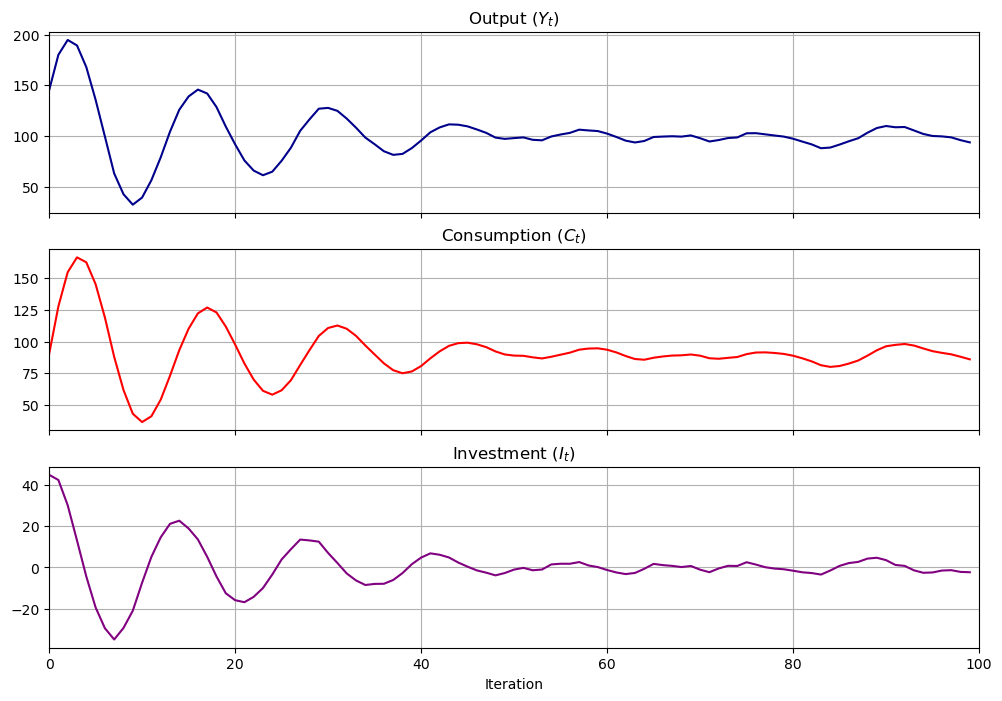

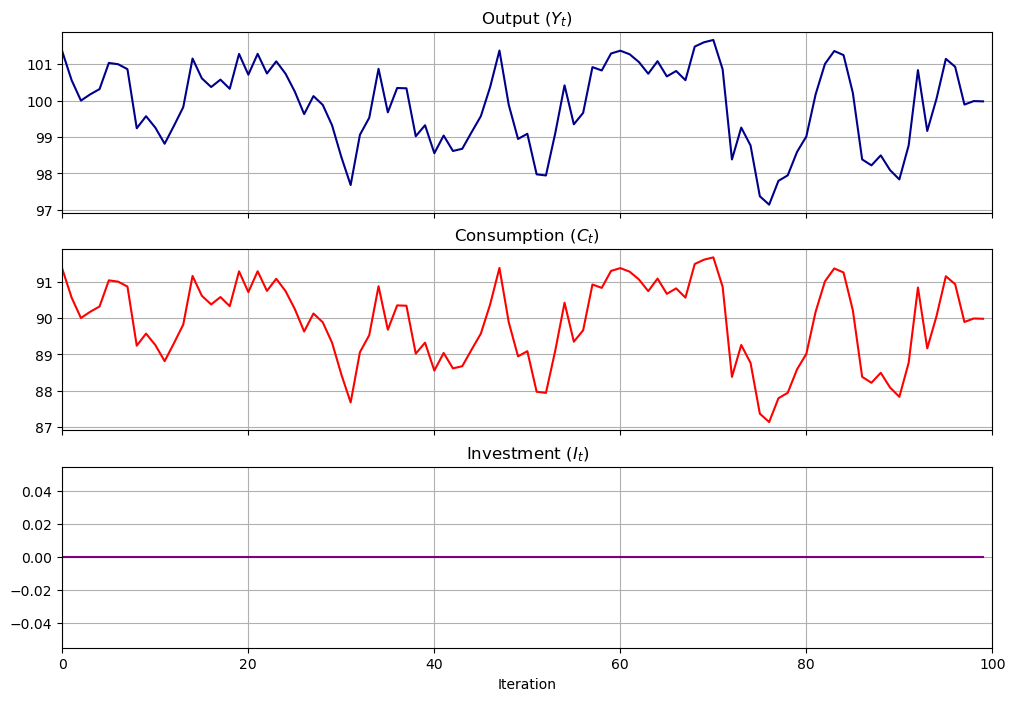

It turns out that we can use the QuantEcon.py LinearStateSpace class to do much of the work that we have done from scratch above.

Here is how we map the Samuelson model into an instance of a

LinearStateSpace class

"""This script maps the Samuelson model in the the

``LinearStateSpace`` class

"""

α = 0.8

β = 0.9

ρ1 = α + β

ρ2 = -β

γ = 10

σ = 1

g = 10

n = 100

A = [[1, 0, 0],

[γ + g, ρ1, ρ2],

[0, 1, 0]]

G = [[γ + g, ρ1, ρ2], # this is Y_{t+1}

[γ, α, 0], # this is C_{t+1}

[0, β, -β]] # this is I_{t+1}

μ_0 = [1, 100, 50]

C = np.zeros((3,1))

C[1] = σ # stochastic

sam_t = LinearStateSpace(A, C, G, mu_0=μ_0)

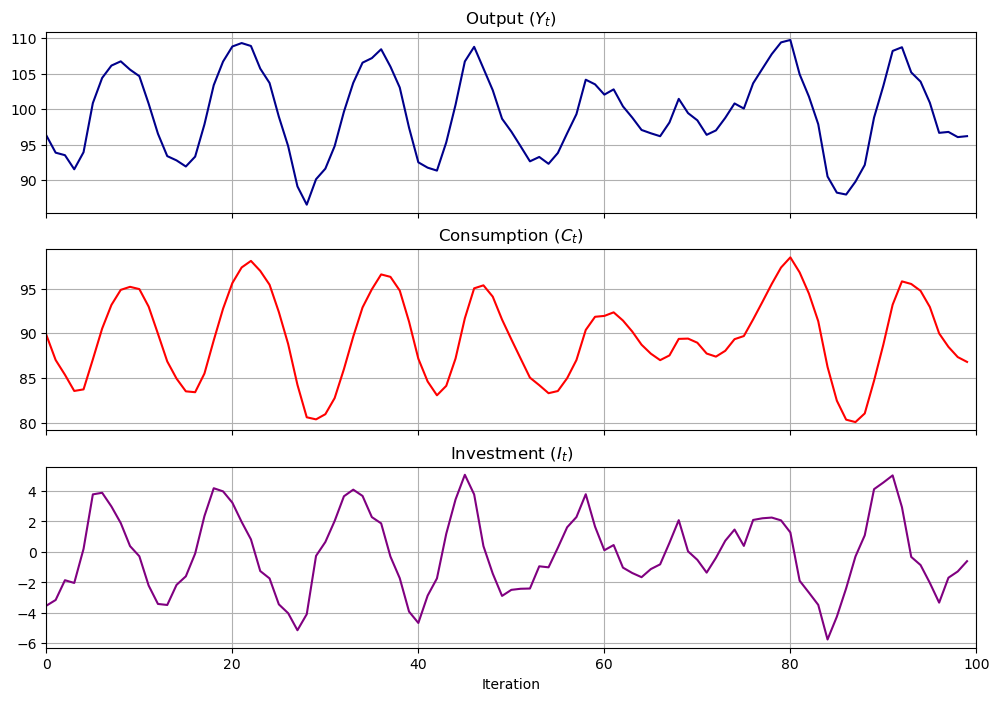

x, y = sam_t.simulate(ts_length=n)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharex=True, figsize=(12, 8))

titles = ['Output ($Y_t$)', 'Consumption ($C_t$)', 'Investment ($I_t$)']

colors = ['darkblue', 'red', 'purple']

for ax, series, title, color in zip(axes, y, titles, colors):

ax.plot(series, color=color)

ax.set(title=title, xlim=(0, n))

ax.grid()

axes[-1].set_xlabel('Iteration')

plt.show()

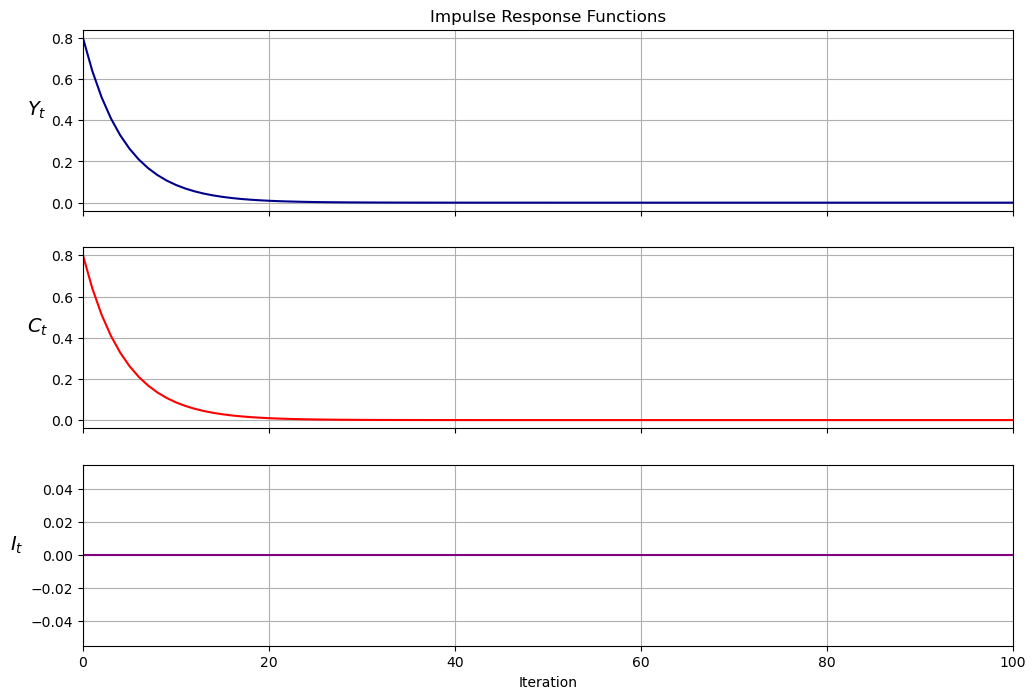

3.7.1. Other Methods in the LinearStateSpace Class#

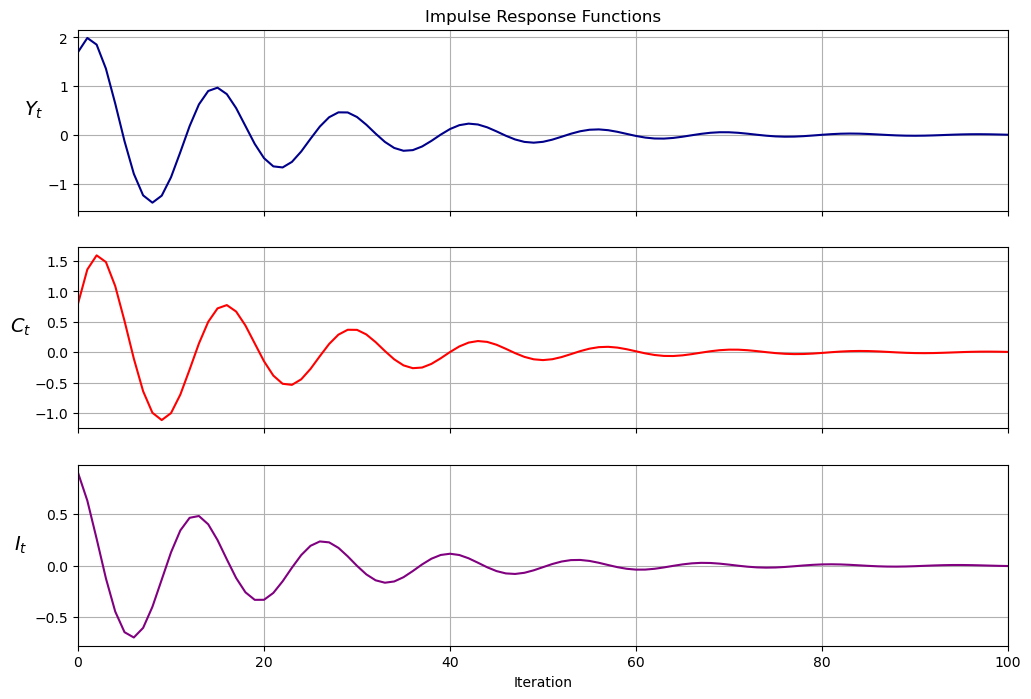

Let’s plot impulse response functions for the instance of the

Samuelson model using a method in the LinearStateSpace class

imres = sam_t.impulse_response()

imres = np.asarray(imres)

y1 = imres[:, :, 0]

y2 = imres[:, :, 1]

y1.shape

Now let’s compute the zeros of the characteristic polynomial by simply calculating the eigenvalues of \(A\)

A = np.asarray(A)

w, v = np.linalg.eig(A)

print(w)

[0.85+0.42130749j 0.85-0.42130749j 1. +0.j ]

3.7.2. Inheriting Methods from LinearStateSpace#

We could also create a subclass of LinearStateSpace (inheriting all its

methods and attributes) to add more functions to use

class SamuelsonLSS(LinearStateSpace):

"""

This subclass creates a Samuelson multiplier-accelerator model

as a linear state space system.

"""

def __init__(self,

y_0=100,

y_1=50,

α=0.8,

β=0.9,

γ=10,

σ=1,

g=10):

self.α, self.β = α, β

self.y_0, self.y_1, self.g = y_0, y_1, g

self.γ, self.σ = γ, σ

# Define intial conditions

self.μ_0 = [1, y_0, y_1]

self.ρ1 = α + β

self.ρ2 = -β

# Define transition matrix

self.A = [[1, 0, 0],

[γ + g, self.ρ1, self.ρ2],

[0, 1, 0]]

# Define output matrix

self.G = [[γ + g, self.ρ1, self.ρ2], # this is Y_{t+1}

[γ, α, 0], # this is C_{t+1}

[0, β, -β]] # this is I_{t+1}

self.C = np.zeros((3, 1))

self.C[1] = σ # stochastic

# Initialize LSS with parameters from Samuelson model

LinearStateSpace.__init__(self, self.A, self.C, self.G, mu_0=self.μ_0)

def plot_simulation(self, ts_length=100, stationary=True):

# Temporarily store original parameters

temp_mu = self.mu_0

temp_Sigma = self.Sigma_0

# Set distribution parameters equal to their stationary

# values for simulation

if stationary == True:

try:

self.mu_x, self.mu_y, self.Sigma_x, self.Sigma_y, self.Sigma_yx = \

self.stationary_distributions()

self.mu_0 = self.mu_x

self.Sigma_0 = self.Sigma_x

# Exception where no convergence achieved when

#calculating stationary distributions

except ValueError:

print('Stationary distribution does not exist')

x, y = self.simulate(ts_length)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharex=True, figsize=(12, 8))

titles = ['Output ($Y_t$)', 'Consumption ($C_t$)', 'Investment ($I_t$)']

colors = ['darkblue', 'red', 'purple']

for ax, series, title, color in zip(axes, y, titles, colors):

ax.plot(series, color=color)

ax.set(title=title, xlim=(0, n))

ax.grid()

axes[-1].set_xlabel('Iteration')

# Reset distribution parameters to their initial values

self.mu_0 = temp_mu

self.Sigma_0 = temp_Sigma

return fig

def plot_irf(self, j=5):

x, y = self.impulse_response(j)

# Reshape into 3 x j matrix for plotting purposes

yimf = np.array(y).flatten().reshape(j+1, 3).T

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 1, sharex=True, figsize=(12, 8))

labels = ['$Y_t$', '$C_t$', '$I_t$']

colors = ['darkblue', 'red', 'purple']

for ax, series, label, color in zip(axes, yimf, labels, colors):

ax.plot(series, color=color)

ax.set(xlim=(0, j))

ax.set_ylabel(label, rotation=0, fontsize=14, labelpad=10)

ax.grid()

axes[0].set_title('Impulse Response Functions')

axes[-1].set_xlabel('Iteration')

return fig

def multipliers(self, j=5):

x, y = self.impulse_response(j)

return np.sum(np.array(y).flatten().reshape(j+1, 3), axis=0)

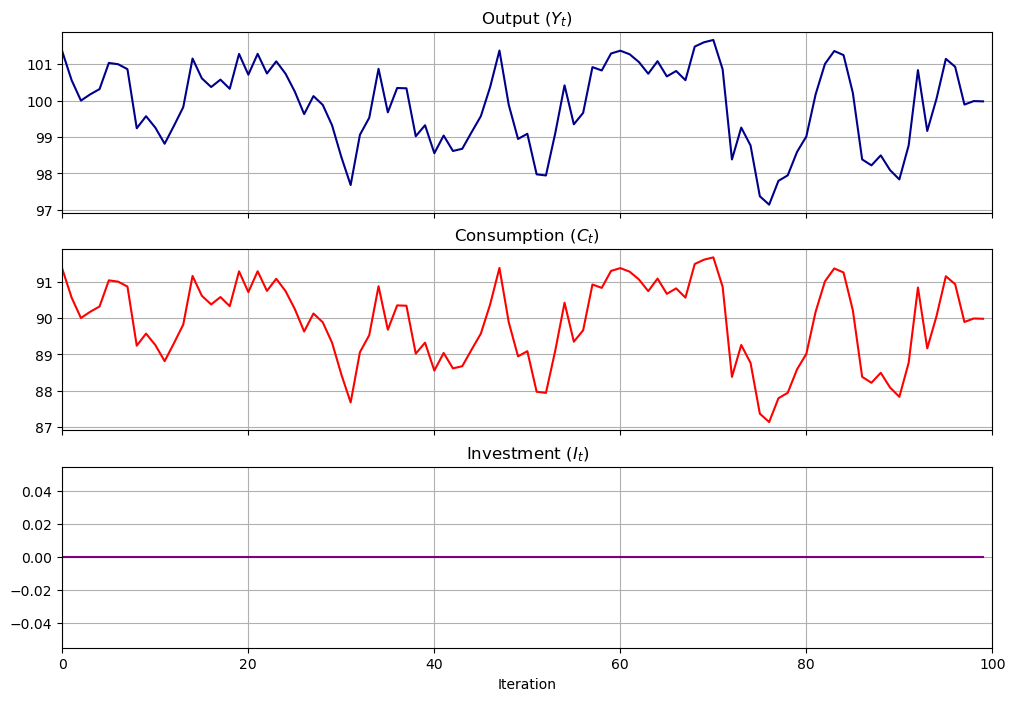

3.7.3. Illustrations#

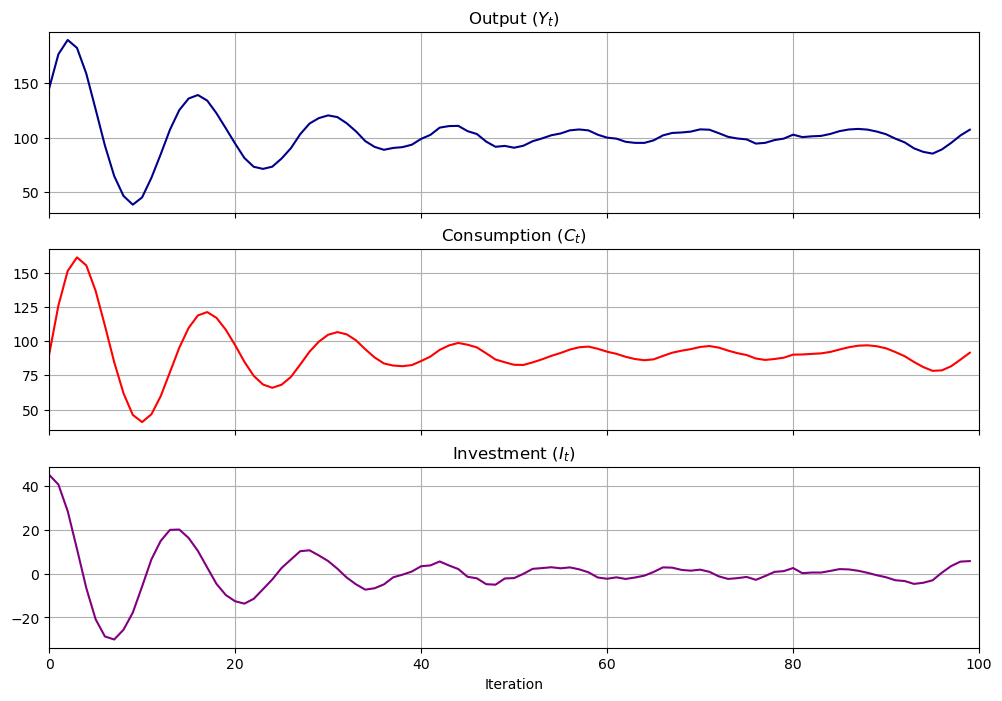

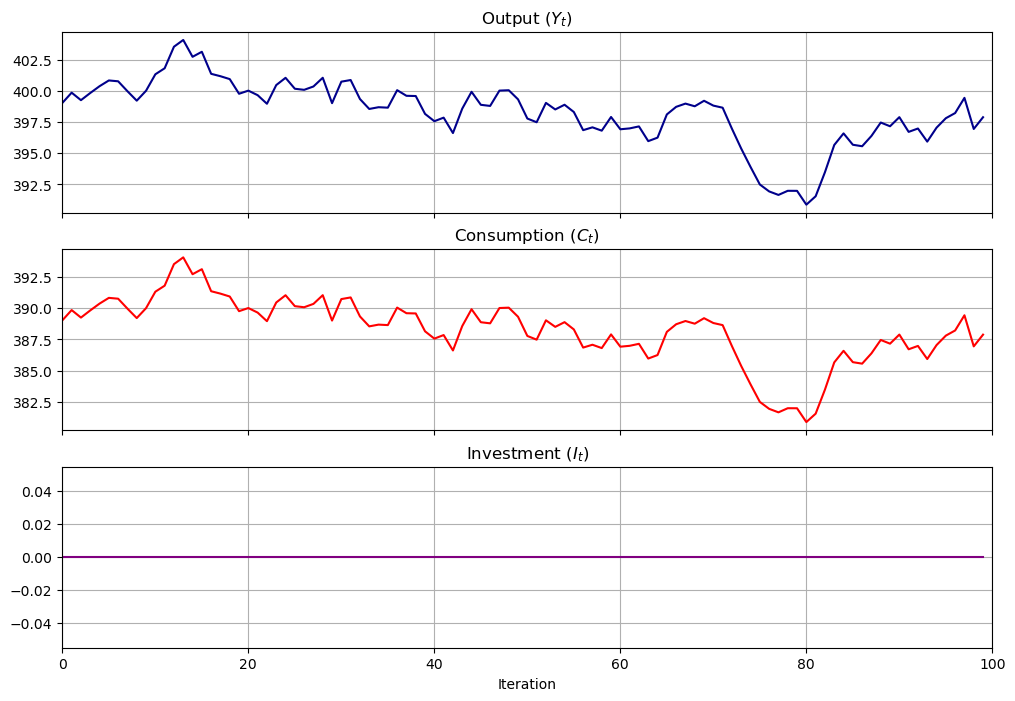

Let’s show how we can use the SamuelsonLSS

samlss = SamuelsonLSS()

samlss.plot_simulation(100, stationary=False)

plt.show()

samlss.plot_simulation(100, stationary=True)

plt.show()

samlss.plot_irf(100)

plt.show()

samlss.multipliers()

array([7.414389, 6.835896, 0.578493])

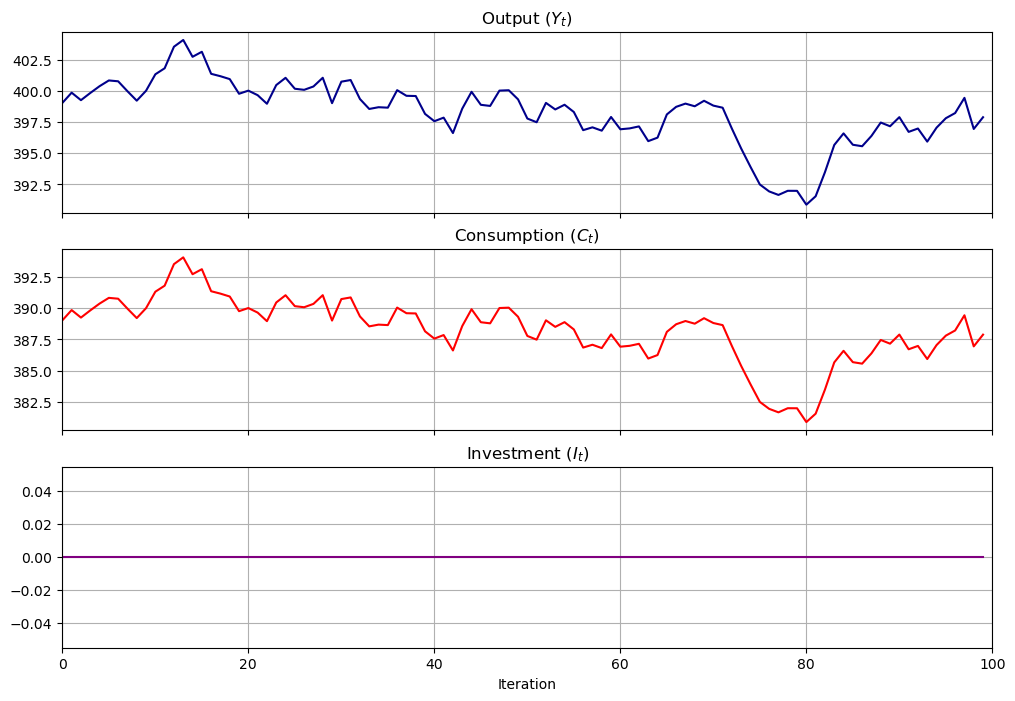

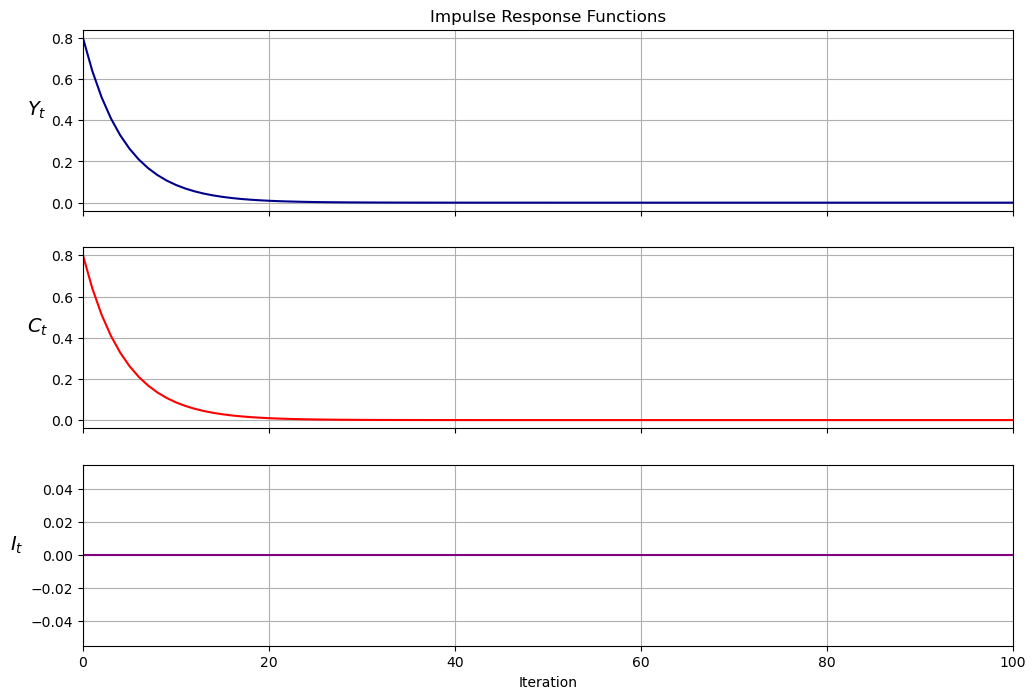

3.8. Pure Multiplier Model#

Let’s shut down the accelerator by setting \(b=0\) to get a pure multiplier model

the absence of cycles gives an idea about why Samuelson included the accelerator

pure_multiplier = SamuelsonLSS(α=0.95, β=0)

pure_multiplier.plot_simulation()

pure_multiplier = SamuelsonLSS(α=0.8, β=0)

pure_multiplier.plot_simulation()

pure_multiplier.plot_irf(100)

3.9. Summary#

In this lecture, we wrote functions and classes to represent non-stochastic and stochastic versions of the Samuelson (1939) multiplier-accelerator model, described in [Samuelson, 1939].

We saw that different parameter values led to different output paths, which could either be stationary, explosive, or oscillating.

We also were able to represent the model using the QuantEcon.py LinearStateSpace class.